In the world of athletics, few stories match the raw human drama of Ana Fidelia Quirot – Olympic medalist, world champion, and survivor of a catastrophe that would have ended most careers. Her journey from Cuban prodigy to global icon, through unimaginable tragedy and back to glory, reads like fiction. Except every astonishing chapter actually happened.

From “La Gorda” to Glory: Ana Fidelia Quirot’s Early Years in Cuban Athletics

It’s almost comical to imagine one of history’s greatest middle-distance runners being nicknamed “La Gorda” (fatty) as a child. But in the eastern Cuban city of Palma Soriano, young Ana Fidelia Quirot Moré wore the moniker well into her elite career – a reminder of humble beginnings that grounded her meteoric rise.

Born in 1963 to parents devoted to Fidel Castro’s revolution (hence her middle name, “Fidelia”), athletics was practically genetic. Her father boxed, her brother ran 400 meters, and her sister played basketball for Cuba’s national team. The revolutionary spirit and sporting excellence were intertwined in the Quirot household like the double helix of DNA.

When Ana Fidelia first stepped onto a track in October 1974, nobody saw a future champion – just another kid trying different events: baseball throw, high jump, long jump, 60-meter dash. But something clicked. Her raw talent caught her professor’s eye, earning her entry into the local sports program.

The turning point came in 1975 when she represented Cuba at an international event in Hungary. While teammates faltered, the twelve-year-old Ana Fidelia stepped up, securing bronze and returning home as the only Cuban medalist. This performance unlocked the door to Cuba’s prestigious EIDE sports school in Santiago under coach Eusiquio Sarior.

Her first trainer, Juan Heredia Salazar, saw something in the girl that others missed. “He recognized my potential early on,” Ana Fidelia Quirot would later recall, “and persistently encouraged both me and my mother to pursue athletics.” In a country where sports represented national identity, Ana Fidelia Quirot had found her calling.

Ana Fidelia Quirot’s Rise: Dominating Middle-Distance Running in 1980s Cuba

By 1983, Ana Fidelia Quirot had joined Cuba’s national athletics team. Her international breakthrough came that same year at the Pan American Games in Caracas, claiming silver in the 400 meters – a distance she would soon complement with her signature 800-meter event.

The 1987 Pan American Games in Indianapolis became her coming-out party. Quirot dominated, capturing gold in both the 400 and 800 meters. Later that year at the World Championships in Rome, she set a new personal best of 1:55.84 in the 800 meters, finishing fourth.

Between 1987 and 1991, Ana Fidelia was nearly untouchable, winning 39 consecutive 800-meter races. Her peak performance came at the 1989 IAAF World Cup in Barcelona, winning the 800 meters in a blistering 1:54.44 – ranking her third on the all-time list. She also claimed gold in the 400 meters, showcasing her versatility and establishing herself as the world’s premier middle-distance runner.

The IAAF recognized her dominance, naming her Female Athlete of the Year in 1989. By 1990, she achieved something no other woman had done repeatedly: ranking #1 globally in both the 400 and 800 meters.

Then came the crushing disappointment of 1988. Undefeated that season and consistently outperforming her rivals, Ana Fidelia Quirot was the overwhelming favorite for 800-meter gold at the Seoul Olympics. Fortune, however, had other plans. Cuba boycotted the Games after the International Olympic Committee refused North Korea’s demand to co-host.

Lesser athletes might have complained about politics stealing their moment. Not Ana Fidelia Quirot. “Principles are more important than gold medals,” she stated, embodying the revolutionary spirit that defined Cuban athletics. Her #1 world ranking that year tells the story of what might have been.

Ana Fidelia Quirot’s Tragic Fire Accident: A Turning Point in Her Career

January 23, 1993. Seven months pregnant, Ana Fidelia was in her apartment doing laundry – a mundane task complicated by Cuba’s economic hardships and resulting shortages. Like many Cubans, she used a small kerosene-powered cookstove.

What happened next would change her life forever.

Believing the stove unlit, she added isopropyl alcohol to hot water in the pot. The alcohol fumes made contact with the burner, igniting instantly. Within seconds, flames engulfed her body.

The damage was catastrophic: severe burns covered 38 percent of her body—face, neck, chest, and stomach. Doctors induced labor prematurely to save her life. Her daughter, Carla Fidelia, survived only one week. As if fate hadn’t been cruel enough, Quirot’s former husband, wrestler Raul Cascaret, died in a car accident around the same time.

Rushed to Havana’s Hermanos Ameijeiras Hospital burn unit, Ana Fidelia’s life hung by a thread. Multiple skin grafts and surgeries followed as Cuba’s healthcare system mobilized to save their national hero.

When she regained consciousness to find Fidel Castro himself at her bedside, her first words revealed the steel within: “I will run again.”

Defying Medical Odds: Ana Fidelia Quirot’s Determined Road to Recovery

Two months after the accident – while doctors still doubted she’d ever walk normally – Ana Fidelia was already riding a stationary bike in her hospital room and running up and down stairs. Hospital staff watched in disbelief as she pushed recovery boundaries, defying medical expectations.

“Thirty-eight percent of my body was affected by second and third-degree burns; it seemed impossible to return to sports. In fact, my life was in danger,” Quirot later remembered. “Of course I remember.”

Released after just three months – another testament to her extraordinary resilience – she immediately sought out coach Leandro Civil to discuss a comeback. “Yes, I asked him, and he never hesitated,” she recalled. “Do you remember those afternoons when Mercedes Álvarez and I would run after the sun set at the ‘Juan Abrantes’ university stadium? Aside from you and my family, few believed in me, in my ability to run again.”

The burns had created severe limitations. Scar tissue restricted movement in her arms and head. Heightened sensitivity to sunlight forced her to train during early mornings and late evenings. But Ana Fidelia Quirot had decided to run again, and nothing – not even the laws of medical science – would stop her.

The Impossible Comeback Begins

Just months after facing death, Ana Fidelia Quirot returned to competition at the 1993 Central American and Caribbean Games in Ponce, Puerto Rico. Her movement still severely restricted by burn scars, she nonetheless claimed silver in the 800 meters.

Media attention focused more on her presence than her performance. Here was a woman who, by all medical logic, should have been happy just to be alive – yet she was already back on the international stage.

Through 1994, she underwent further surgeries while maintaining a brutal training regimen. The physical toll was immense, but the psychological burdens were equally heavy – grief for her lost child, adjustment to her changed appearance, the constant pain of rehabilitation.

“Today, I am still grateful to Cuba’s medical system, to the psychologists and the doctors in the multi-disciplinary team at the Hermanos Ameijeiras Hospital, to my family and friends,” she would later say.

Her remarkable resurgence culminated at the 1995 World Championships in Gothenburg, Sweden. In the 800-meter final, Quirot deployed tactical brilliance, surging from fifth place to claim gold in 1:56.11. The victory seemed almost supernatural – a Phoenix rising literally from the flames.

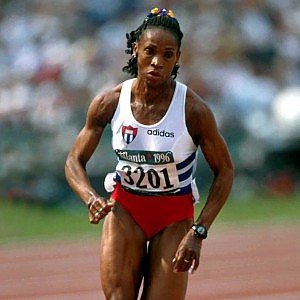

Atlanta 1996: Ana Fidelia Quirot’s Olympic Silver and Emotional Victory

The 1996 Atlanta Olympics provided the next chapter in Ana Fidelia’s extraordinary journey. Four years earlier in Barcelona, she had claimed bronze in the 800 meters while grieving her recently deceased coach, Blas Beato.

Now in Atlanta, still bearing the physical and emotional scars of her accident, she captured silver with a time of 1:58.11. For any other athlete, Olympic silver would be a career highlight. For Quirot, it carried the bittersweet taste of what might have been.

“I think I made tactical errors that cost me gold,” she later reflected. Yet considering the journey that had brought her to that Olympic stadium – from the burn unit to the podium in just three years – silver represented something far greater than athletic achievement.

Her story of resilience and revival transcended sport. Ana Fidelia Quirot had become something more than a champion runner. She embodied human possibility in its purest form.

Defying Logic, Defining Greatness

The final exclamation point on her miraculous comeback came at the 1997 World Championships in Athens. Approaching her mid-30s—ancient by elite middle-distance standards—and still dealing with the physical limitations from her burns, Ana Fidelia Quirot successfully defended her world title, winning gold in 1:57.14.

This victory established her fourth #1 world ranking in the 800 meters, her first since the accident. Despite her main rival Maria Mutola winning more head-to-head races that year, Quirot’s victories in the most significant events – including the World Championship and Grand Prix Finale – secured her the top position.

Consider these numbers: Before the accident, her personal best was 1:54.44. After suffering burns over more than a third of her body, she still managed to run 1:56.11 to win her first world title. Medically speaking, this shouldn’t have been possible.

For context, compare her comeback to other legendary sporting returns: Niki Lauda‘s miraculous return to Formula One after a near-fatal crash or Bethany Hamilton continuing her surfing career after losing an arm to a shark attack (read her story here). Ana Fidelia’s revival stands among the most extraordinary in sports history.

National Hero, Global Inspiration

In Cuba, Ana Fidelia Quirot is more than just an athlete -she’s a national hero who symbolizes the resilience of the Cuban spirit. She embraced this role, viewing herself as “a symbol of the Cuban Revolution, its achievements in education, medicine, and sports.”

Fidel Castro held her in the highest regard, referring to her comeback achievement as a “diamond medal” and attending her retirement ceremony in 2001. She served as an unofficial ambassador for Cuba, embodying revolutionary ideals through her perseverance.

Beyond Cuba’s borders, Ana Fidelia is recognized as one of the greatest 800-meter runners ever. Her personal best still ranks among the top performers in history. In recognition of her legacy, she donated her 1997 World Championships winning bodysuit to the IAAF’s Athletics for a Better World project.

Legacy of Ana Fidelia Quirot: A Story of Courage, Comeback, and Human Spirit

Ana Fidelia Quirot’s journey from Cuban prodigy to world champion, from near-death to the pinnacle of athletic achievement, represents something rare in sports – a story that transcends competition to illuminate the boundless capacity of human determination.

Her legacy isn’t merely in records or medals. It’s in the impossible becoming possible. It’s in the pursuit of excellence when merely surviving would have been achievement enough. It’s in redefining what we believe humans can endure and overcome.

“I can’t ask more of life,” Quirot once said, reflecting on her extraordinary journey. Perhaps not – but her life continues to ask more of us: to reconsider our limitations, to question our assumptions about recovery and resilience, and to understand that the human spirit, when tested by fire, can emerge not just intact but transformed.

In Cuban sports lore, in Olympic history, in the annals of human achievement, Ana Fidelia Quirot stands as the Phoenix who literally rose from the flames – proving that sometimes the greatest victories happen far from any finish line.